Reasoning from a Price Change

Too many commentators are making an elemental error that the economist Scott Sumner has persistently warned us about

The idea that interest rates are some kind of automatic economic stabilizer has gained wide credence this cycle. Many seem to believe that the Fed can just sit back – at just about any funds rate it wants – and let the interest rate markets trade to whatever levels are needed to guard the economic soft-landing (which again, we’ve been in for 18 months now – this is the soft landing).

This all sounds reasonable on a surface level until you realize that it’s not how it’s ever worked before.

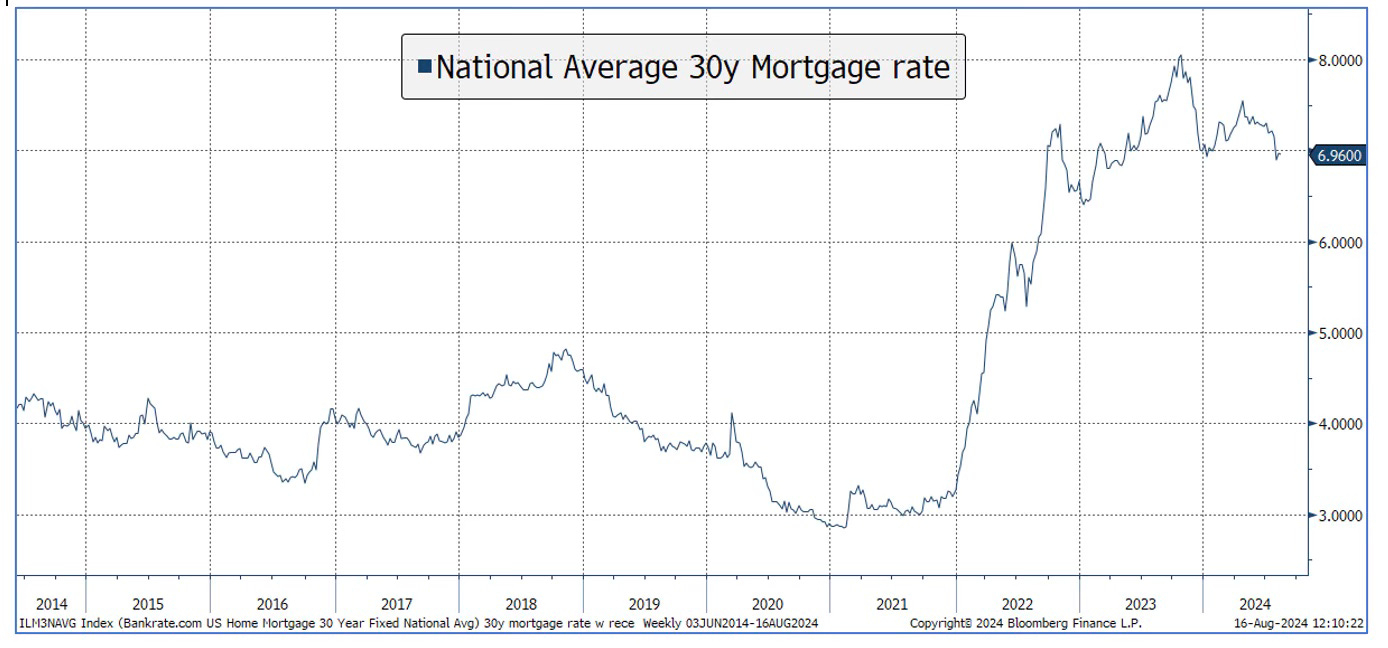

A case in point is the 100bp drop in mortgage rates that has many speculating that a housing resurgence is right around the corner.

The assumption that a lower mortgage rate must bring increased housing activity is an elemental error in thinking that the economist Scott Sumner refers to as “reasoning from a price change.”

Here’s Sumner in 2014:

I don’t know how many times I have to keep saying this before the rest of the profession figures it out. Never reason from a price change. It makes no sense to argue whether a higher price will increase or decrease quantity. Here is a S&D diagram. I dare you to show me how price changes affect quantity.

And here is an IS-LM diagram. Interest rates are the price of credit. Changes in interest rates do not have any effect on quantity of output, price of output, or any other variable. It’s not even an “other things equal” deal; price changes have no effect.

At this point some economists will say; “I meant an interest rate change caused by a change in monetary policy.” The problem is that higher interest rates can be produced by both easier and tighter monetary policy. And easier and tighter monetary policy have opposite effects on prices and output. So I’m sorry, but it’s still a meaningless debate. It’s not that there is a right or wrong answer; there is no coherent question. Monetary policy can shift the LM curve, the IS curve, or both.

It's a powerful truism of market economics, in which prices are determined by supply and demand in competitive markets: prices don’t “cause” anything. The price is simply where the supply and demand curves intersect. Supply and demand “cause” price, not vice versa.

The contention that “lower mortgage rates will bring a stronger housing market” embeds an implicit assumption that the decline in mortgage rates is the result of an increase in the supply of mortgage credit as opposed to a drop in the demand for mortgage credit. Yet in reality we have no way to be sure which of those caused the decline in mortgage rates, or whether both played a part.

This is the root of my contention with the financial conditions obsession. The theory that financial conditions indices - which include interest rates – should have a consistently causal relationship to economic growth implicitly reasons from a price change though the embedded assumption that lower interest rates should bring stronger growth.

Yet, at the end of every economic cycle we see declines in interest rate driven not by an expansionary supply of credit but by a collapse in the demand for it. What follows we call “a recession.”